***

In her pre-show interview, festival honoree Laura Linney and her interlocutor both praised her excellent 2000 film You Can Count on Me and its screenwriter/director Kenneth Lonergan. Tamara Jenkins assumes these duties on The Savages, which isn't bad, but it takes a while to find its somewhat shaky footing.

Jenkins directs her leads well (though she doesn't quite know what to do with Philip Bosco), particularly as they perform the "spontaneity" of the drama's most telling moments. It is here that the score and, to a lesser extent, the photography, let the side down, as they telegraph these moments as little punchlines, cuing audience titters.

Linney spoke insightfully of the theater (i.e. live plays), and one supposes that this association (Linney plays an aspiring playwrite and Philip Seymour Hoffman a dramatic theorist) explains the selection of The Savages for her tribute. But for all its references to Brecht (and Genet, and O'Neill), this jell never quite sets.

2007 wasn't a great year for film prints. This appeared to be a typical high-speed print for multiplex consumption, a few generations removed from the film-out of a digital intermediate. Reel 2 was full of little red dice-dot patterns to thwart surreptitious camcorder artists. (Corner-cutting efficiencies and paranoiac interventions persist, in different forms, in the digital age.) Add to that a smattering of scratches and platter wear.

***

In her longest film to date (just shy of an hour on ybca's projectors), The Grand Bizarre, Jodie Mack continues her project of activating patterned surfaces by animation of a sort. Rapid-fire montages of printed, woven, and stitched fabrics give ground to maps and exotic typographies, and are often situated outdoors, in far-flung locales, and embedded amidst modes of transport. Her stop-stasis technique captures a staccato of falling dusk and encroaching shadows; we measure the progress of her work against the rhythms of man (in absentia), machine, and mother nature.

|

A musique concrète soundtrack, composed, like every other aspect of the film, by Mack, propels us through her non-narrative, and sometimes refers to the human cultural production implicit in the film.

I arrived to this screening severely bummed out, having just learned of the Notre-Dame fire. At film's end, it occured to me I hadn't thought about it once the previous hour. I've never cottoned to the idea of film as an essentially escapist medium, but there you have it. Of the two new 35mm features I've seen this year, I found this one far more rewarding than the execrable Knife + Heart.

***

Next up, a couple more award presentations, featuring conversations with the honorees and film screenings tacked on as afterthoughts. I'm inclined to resent the imposition on my time, but sometimes the conversations are edifying.

I had never heard of George Gund award recipient Claude Jarman, Jr., despite apparently having seen him in Fair Wind to Java. I learned that, after his career as a juvenile actor, he served more than a decade as executive director of this very festival, and that during his tenure the festival moved from the Masonic Auditorium to the Palace of Fine Arts due to a controversy over Mai Zetterling's Night Games that led her one-time heroine Shirley Temple to resign from the board (I didn't know she was ever on it!). Pure gold. A conversation afterwards with fellow film enthusiast David Wong (a frequent corrector of the Bay Area Film Calendar whose film fanatic bona fides predate mine considerably) gave me further context and details of the personages involved.

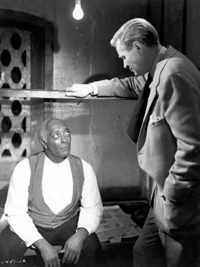

Jarman was 15 or so when he portrayed Chick Mallison in Clarence Brown's Intruder in the Dust (adapted from Faulkner). All racial-justice narratives are products of their times, and I found Intruder's take to be a more interesting reflection on and response to its era than that of To Kill a Mockingbird, with its as-far-as-we-knew unbearably saintly Atticus Finch, 13 years later (and like Intruder released shortly after the novel from which it was adapted). Here, though Chick's lawyer uncle agrees to take the case of accused white-man-back-shooter Lucas Beauchamp (pioneering black Puerto Rican actor Juano Hernandez) with the best intentions, his effort is weighted with prejudice, and Beauchamp knows it.

The film seems to capture a transitional moment: Chick treats his friend Aleck (conventionally portrayed by Elzie Emanuel as a bug-eyed caricature) more or less as an equal despite the master-servant relationship of their respective families. He will grow up more enlightened than his parents, but there's a good chance he'll eventually end up behind the curve of progress himself.

|

Jarman argued that Intruder was a sort of proto-vérité effort due to studio constraints: black and white all-location photography, an absence of scoring that demands actions speak on their own. They don't always speak eloquently, but the film offers an illuminating look at the intersection of race and justice in 1949 and the limits of its depiction.

***

I had never heard of BBC Arena but among the cognoscenti who pick the recipient of the Mel Novikoff award it is apparently deemed an outstanding producer of TV documentaries and has a legendary logo. It is symptomatic of the current (and irreversible?) conflation of cinema and television that this outfit has won an award honoring film exhibitors. Then again, Wisconsin Death Trip did enjoy a very limited theatrical release in 1999 and the 35mm print screened here proves it.

However, the print is no great shakes. The majority of the film consists in black and white restagings of 1890's events based on photographs and headlines from Black River Falls, WI. These are interspersed with color scenes from the present day (20 years ago). To accomodate this, the black and white material was printed on color stock, and of the five reels, only the third managed to look at all like real black and white, and even then the footage had a "posterized" effect (i.e. poor color depth).

Certain throughlines connect the seasonally-ordered vignettes, such as admissions to the local booby hatch, and the exploits of a compulsive window smasher and a fake opera singer. But the quirky-quaintness of it all wears thin after a while. I could have used some of the personal voice, not to mention the shameless balderdash, of Guy Maddin's My Winnipeg.

***

So what were the best films I saw during the festival? Blood for Dracula and Gallipoli! Both of them in decades-old, faded prints, and neither a part of the festival. Life goes on!